Opinion: The Energy Charter Treaty needs a serious overhaul

Anna Cavazzini, Chair of the Investment Monitoring Group of the European Parliament

Strategic litigation against the energy transition – the Energy Charter Treaty needs a serious overhaul

The European Commission published its proposal for the reform of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) on May 28, 2020. Over the last few years, the treaty has attracted the anger of governments and climate campaigners alike for its overly broad protection of energy investments, and its special arbitration tribunals to settle disputes.

Cases under this treaty have led to large damages awards against States, regularly reaching hundreds of million and up to several billion Euro of taxpayers money. Critics rightly worry that the ECT is a powerful tool in the hands of large oil, gas and coal companies to dissuade governments from making the transition to clean energy, or to make them foot the bill.

The Energy Charter Treaty protects fossil energy investments and allows investor-state disputes that can target action of governments trying to become carbon neutral. This is incompatible with goals of the EU Green Deal and the Paris agreement.

In July 2019, the European Commission received a mandate to modernise the outdated treaty. A first round of negotiation took place in December 2019. Talks are set to resume after the first wave of the covid19 pandemic, with rounds scheduled for July and October 2020. The publication of the EU proposal is a very welcome step enabling the European Parliament and civil society to monitor the process.

One of the Commission’s aims is to ensure that the ECT does not stand in the way of fighting climate change. The reform proposal contains language trying to limit protection standards which have led to outrageous cases in the past, new provisions on climate and sustainable development, and changes in procedural rules to adjudicate disputes. Doing so, the Commission is leading internal efforts to mitigate the harm that can be caused by the Treaty to its State parties, their budgets and their transition efforts.

However, there are reasons to stay alarmed. The proposal still allows investors to sue governments if they consider that a law harms the profitability of their investment. It still does not cap damages, meaning that the price tag for some policies aiming at fighting climate change might still explode. It still protects energy investors way beyond what national law and constitutions give to all other actors. It is still one-sided, with only rights for energy investors to sue states, but no enforceable obligations to lower their emissions or respect human rights in relation to their investment. It still provides investors with a powerful lobby tool with which to threaten governments – like in the recent case of Fortum-backed German investor Uniper, threatening the Dutch coal exit plan on the basis of the Energy Charter Treaty.

The proposal does not either include a supremacy clause, putting the Paris Climate agreement and its implementation in European and national policies out of the reach of investment lawsuits under the ECT, nor does it provide satisfactory carve-outs for climate policies.

More importantly, the Commission’s well meaning proposal will have to be accepted by all other members of the Treaty before becoming reality. Those are over 5O countries including Kazakhstan or Japan, which have not signalled any interest in meaningfully reform. Even if the EU proposal passes this hurdle, arbitrators have had the disturbing tendency to ignore changes to the system – up to decisions from the European Court of Justice.

When assessing the Commission’s proposal, one has to go back to fundamentals. Do we need the Energy Charter Treaty? There is no proof of a positive effect on sustainable investment of the Treaty. On the other hand, the risks and liability it brings to the EU, to Member States, their budget and policies are well documented.

The Commission’s efforts are commendable, and attempt to fix a broken treaty. But this attempt must not drag on for years. We cannot afford to keep on protecting dirty investments.

The profile of the Energy Charter Treaty is rising thanks to powerful campaigns by civil society organisations, new cases that keep on piling up, and an appetite for change in the Commission, the European Parliament and the Council. The Council has for example recently committed to soon deal with the legality of the Intra-EU application of the Charter – when EU investors use the treaty to sue EU member States. A termination of this application would already make a large number of disputes impossible.

I call on all relevant actors and institutions to engage and work together to ensure that the Energy Charter Treaty does not constitute a costly obstacle in our path towards a carbon neutral continent.

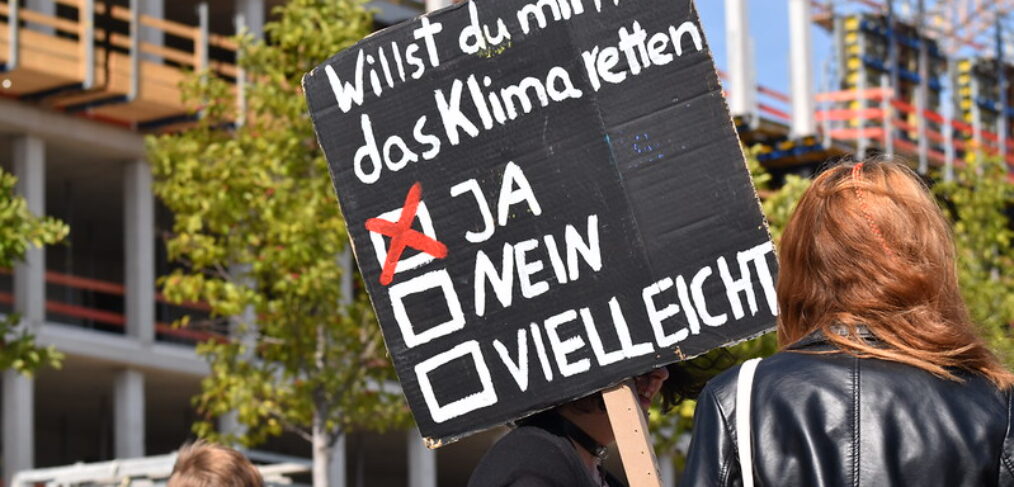

Photo: Fridays for future Duisbourg (CC BY-SA 2.0)